Take a walk with us through the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library and explore some incredible illustrations.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2022 issue of The Northern Light.

Written by Hilary Anderson Stelling, Director of Exhibitions and Collections, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library.

In 1797, French-born artist Thomas Bluget de Valdenuit designed a Masonic apron while working in New York City. Soon after, he returned to France, but his apron design lived on in the United States. One of de Valdenuit’s aprons served as a model for an embroidered Masonic apron probably made by a female relative of its original owner in the early 1800s. This unknown needlewoman wrought her colorful interpretation of de Valdenuit’s design in silk thread on a silk body. Adding her own flourish to the design, she selected colors for the different symbols and ornamented her version with a border of a delicate green vine studded with pink and white flowers.

Like the embroiderer who crafted the apron in New York, artisans of all kinds have often looked to printed depictions of Masonic Symbols and concepts as inspiration for their own creations in the 1700s and 1800s. During this time, printed representations of Masonic emblems took many forms, including certificates, summons, aprons, and book illustrations. Because they were printed on easily portable objects and documents, in the early 1800s, these works traveled with their owners. These printed images were easy to find and share in areas where Freemasons were active. Publications and certificates issued or endorsed by Masonic organizations also had the advantage of being considered reliable—or even official—portrayals of Freemasonry’s extensive visual language.

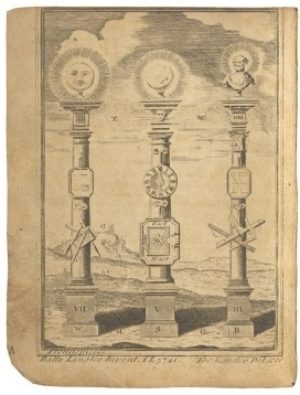

To help make them appealing to consumers, some Masonic publications contained attractive frontispieces and illustrations. Artists used these images for inspiration again and again when creating aprons, jewels, and other objects for Freemasons. This painted apron above, bearing an image of columns topped with the sun, the moon, and the Worshipful Master, uses elements from the frontispiece of a builder’s textbook, The Builder’s Jewel: or, the Youth’s Instructor and Workman’s Remembrancer, that was first published in England in 1741. Thomas Langley, an artist, and the author’s brother included many Masonic symbols in the illustration opposite the book’s title page, even though the text did not discuss Freemasonry. Like the artist who painted the apron, the engraver who incised this silver mark medal in the early 1800s looked to Langley’s illustration—or an object that featured elements of Langley’s image on it— for inspiration. He made the design of this medal his own by changing some elements, adding symbols, and ornamenting the distinctively shaped hanger on the medal with piercing.

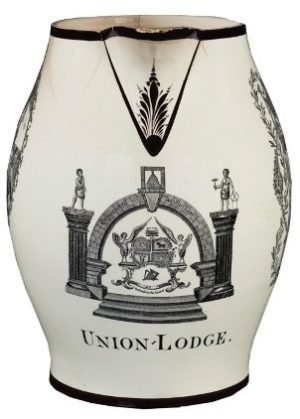

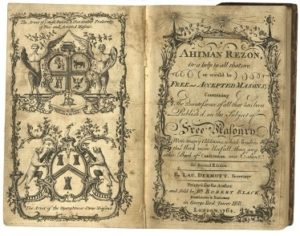

In 1811, sea captain and merchant Nehemiah Wright Skillings gave a pair of specially commissioned earthenware pitchers made in England to Union Lodge in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Personalized with the name of the lodge, these pitchers bore transfer-printed images of Masonic symbols and scenes. Under each spout, a decorator positioned prints of a Masonic emblem, the arms of the Ancients, at the center of an arch flanked by columns. This emblem had become familiar to many Freemasons as part of the frontispiece to Ahiman Rezon, a Masonic publication first issued in 1756 and reprinted many times. By the early 1810s, these arms had become a familiar image in Masonic iconography and would have been readily recognized by Skillings’ Brethren in Union Lodge.

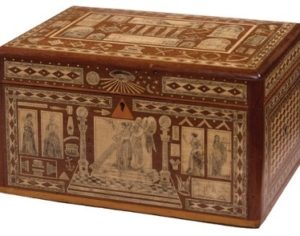

Soon after Skillings presented his gift to his lodge, Connecticut-based lecturer and writer, Jeremy Ladd Cross, first offered his Masonic handbook, The True Masonic Chart, to the public. Working with fellow Freemason and engraver Amos Doolittle, Cross Published this work in 1819. It stood out among other Masonic guides available at that time. The True Masonic Chart gave readers something out-of-the-ordinary -- 39 pages of illustrations of scenes, symbols, and lodge furnishings. Cross published multiple versions of this work over his lifetime. Images in The True Masonic Chart served as models for the artist who embellished this lockable wooden cash box in 1860 or 1861.

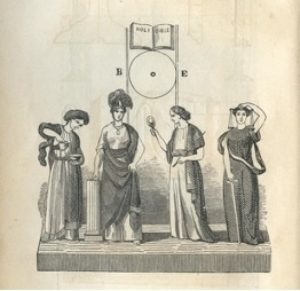

The artist used plates in Cross’s work as models for the multitude of pictures inked onto the surface of this box. These pictures include an image of the Masonic virtues of Temperance, Fortitude, Prudence, and Justice, similar to the one that appeared in an edition of Cross’s work released in 1851. The artist penned symbols and scenes from The True Masonic Chart directly onto the smooth material inlaid on the box to create this striking object. Though the inlay on the box resembles ivory or bone, it is made of sulfur or light-colored putty, a decorative technique that was popular in Pennsylvania in the early to mid-nineteenth century.

Artists and craftsmen working for the Masonic clientele in the 1800s drew not only from their knowledge of the symbols of Freemasonry and their imaginations to create aprons, jewels, and lodge furnishings, they also relied on the books and documents that Freemasons employed to share ideas and information with their Brethren.

If you would like to learn more about the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library collection, visit their online collection database here.

Looking to learn more about Masonic aprons? Check out our Masonic Apron Resource Library.

Related Stories

Discover additional Scottish Rite blogs and news on this topic.

-

A Jolly Masonic Mug

History

Read More about A Jolly Masonic Mug

-

Manly P. Hall: Philosopher, Mystic, and Freemason

Famous Masons

Read More about Manly P. Hall: Philosopher, Mystic, and Freemason

-

What Does the Beehive Mean in Freemasonry?

Degrees

Read More about What Does the Beehive Mean in Freemasonry?