Explore the inspiring life of Brother James Monroe, the fifth President of the United States, whose leadership and commitment to unity reflect the enduring values of Freemasonry.

“National honor is national property of the highest value” – President James Monroe, first inaugural address

As a Freemason, President James Monroe sought to bring Americans together in the spirit of harmony and purpose, even envisioning an end to partisan politics entirely. His commitment to bridging division echoed our Masonic values of Brotherhood, collaboration, and the pursuit of a common good. Brother Monroe is part of a distinguished line of Presidents who were Freemasons, including Brothers George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and Gerald Ford. Like these leaders, Monroe brought the principles of the Craft into the public sphere, embodying leadership and fraternity during critical moments in American history.

Brother Monroe was a key figure in shaping the early United States, bridging the revolutionary era and the foundational years of the Republic. He held numerous roles, including ambassador, governor, senator, and cabinet secretary, which helped him develop a broad understanding of the nation's needs. Before Brother Monroe became a symbol of unity, he faced challenges that shaped his character and instilled in him a sense of duty and commitment to public service—traits that would later align seamlessly with his Masonic ideals.

Early Life and Education

James Monroe was born on April 28, 1758, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, to Spence Monroe and Elizabeth Jones. Brother Monroe grew up in a family that valued independence, patriotism, and hard work—qualities that would shape his life and resonate deeply with Masonic values. He had one sister, Elizabeth, and three younger brothers, Spence, Andrew, and Joseph Jones. His father was an ardent supporter of liberty, participating in protests against the Stamp Act, while his mother came from a prominent family in King George County.

At age 11, Brother Monroe attended Campbelltown Academy, the best school in the county, and later advanced to the College of William & Mary, where he took courses in Latin and mathematics. In 1772, both of Brother Monroe's parents died, leaving him responsible for his younger brothers at just 16. His uncle, Joseph Jones, worked in public service as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses and helped guide Brother Monroe, paying off family debts and introducing him to prominent figures like Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and George Washington.

During this time, opposition to British rule in the colonies was growing, and Brother Monroe, along with his classmates, joined others in demanding the return of gunpowder confiscated by British authorities. These demands reached a fervor that culminated in Brother Monroe and his fellow militiamen storming the Governor's Palace on June 24, 1775, where they captured several hundred muskets and swords. These actions marked the beginning of Brother Monroe's commitment to American independence and his dedication to public service—values that would define his leadership throughout his life.

Monroe the Mason

A few months after this raid, James Monroe, not yet 20 years of age, joined our venerable Brotherhood. He became an Entered Apprentice in Williamsburg Lodge No. 6 at Williamsburg, VA., on November 9, 1775. Although there is no record of his completing the other two degrees, the records of Cumberland Lodge no. 8 in Tennessee, June 8, 1819, show a reception for Brother Monroe as “a Brother of the Craft,” so there is speculation he did go on to become a Master Mason in 1776. Despite our limited knowledge of his accomplishments in the Craft, we know that on August 22, 1820, Brother Monroe attended the cornerstone ceremony of the District’s first City Hall - now the District’s Court of Appeals Building.

In the Continental Army

In early 1776, Brother Monroe left college and joined the 3rd Virginia Regiment in the Continental Army. As literacy was valued among officers, he was commissioned as a lieutenant, and after training for several months, was called north for the New York and New Jersey campaign. His regiment played a central role in the Continental Army's retreat across the Delaware River on December 7, following the loss of Fort Washington.

Later that same month, Brother Monroe took part in the surprise attack on a Hessian encampment at the Battle of Trenton, where he was severely wounded, nearly dying from a severed artery. General Washington recognized Brother Monroe for his bravery and promoted him to captain. He was sent back to Virginia once healthy to recruit his own company of soldiers. However, he could not recruit soldiers due to lack of resources that would incentivize men to enlist.

Instead, he rejoined the front as part of General William Alexander, Lord Stirling's staff as an auxiliary officer. During the Battle of Brandywine, he forged a close friendship with fellow Freemason, the Marquis de Lafayette, who inspired him to see the war as part of a larger fight against tyranny. Brother Monroe then served in the Philadelphia campaign and endured the infamously harsh winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge. He advanced to major and served as Lord Stirling's aide-de-camp during the Battle of Monmouth.

After another failed attempt to take command of a regiment in Virginia, Brother Monroe heeded his uncle’s advice and resumed his studies at the College of William and Mary under Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson, who became a lifelong friend and mentor. Jefferson encouraged Brother Monroe to pursue a political career, introducing him to influential writings, particularly those of Epictetus.

With British forces increasingly targeting the Southern colonies, Brother Monroe accompanied Jefferson when Virginia's capital was moved to Richmond. Jefferson appointed him as a military commissioner to maintain communication with the Southern Continental Army and the Virginia Militia. By late 1780, Brother Monroe was at last given command of a regiment but was still unable to raise an army. Due to an excess of officers in both the Continental Army and Virginia militia, Brother Monroe did not participate in the Yorktown campaign or the Siege of Yorktown with his friend the Marquis, which proved to be a major source of frustration for him.

Law and Politics

Brother Monroe resumed his law studies under Thomas Jefferson until he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1782. The following year, he was elected to the Confederation Congress, where he served until 1786, all the while advocating for western expansion. He played a key role in the passage of the Northwest Ordinance, which established governance for territories west of Pennsylvania and north of the Ohio River.

In 1786, Brother Monroe married Elizabeth Kortright, with whom he had three children, settling briefly in New York City before returning to Virginia, where he passed the bar exam and became a state attorney. He was soon re-elected to the Virginia House of Delegates and then ran against James Madison for a seat in the 1st United States Congress but lost narrowly.

It didn’t take long for him to enter Congress, however, as he was elected to the Senate following the death of Senator William Grayson. Here, Brother Monroe aligned with Thomas Jefferson against Alexander Hamilton's vision of a strong central government and quickly became a prominent leader in the emerging Democratic-Republican Party.

A Leader at Home and Abroad

As the 1790s progressed, Brother Monroe's career was focused more and more on foreign diplomacy. President Washington sent him to France as ambassador to strengthen relations with the revolutionary government. He successfully secured the release of American prisoners and helped negotiate U.S. navigational rights on the Mississippi River. However, the Jay Treaty with Britain, signed without Brother Monroe's knowledge, strained relations with France and ultimately led to Brother Monroe's recall in 1796.

In 1799, Brother Monroe took yet another step forward in his political career when he was elected Governor of Virginia, a position he used to support education, infrastructure, and militia training in the state. Shortly after his gubernatorial term, he was again sent to France, this time by President Jefferson, to help negotiate the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States. Brother Monroe then served as ambassador to Great Britain, tasked with addressing the impressment of American sailors. Despite some diplomatic successes, Jefferson rejected the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty, which led to increased tensions with Britain, contributing to the War of 1812.

In 1808, Brother Monroe ran unsuccessfully for president against James Madison, partly fueled by his frustration with Jefferson’s handling of foreign treaties. Although he lost, his diplomatic efforts and commitment to public service set the stage for his later achievements as President.

President #5

Brother Monroe’s ambition and energy, together with the backing of President Madison, made him the Republican choice for the presidency in 1816. With little Federalist opposition, he easily won re-election in 1820. His experience as a diplomat in France and Britain, combined with his pragmatic leadership, helped him navigate complex international landscapes while prioritizing the young nation’s interests. Brother Monroe’s push for unity, a key pillar of his presidency, reflected his broader political philosophy throughout his career: the belief that the United States could only thrive if its people and their government worked together towards common goals.

Early in his administration, President Monroe undertook a goodwill tour that marked the beginning of an “Era of Good Feelings,” a period characterized by a sense of national purpose and unity following the War of 1812. During this time, the Federalist Party collapsed, bringing an end to the intense partisan disputes between the Federalists and the dominant Democratic-Republican Party, and Brother Monroe worked to reduce partisan divisions by making nominations that were less focused on party affiliation, intending to eliminate political parties from national politics.

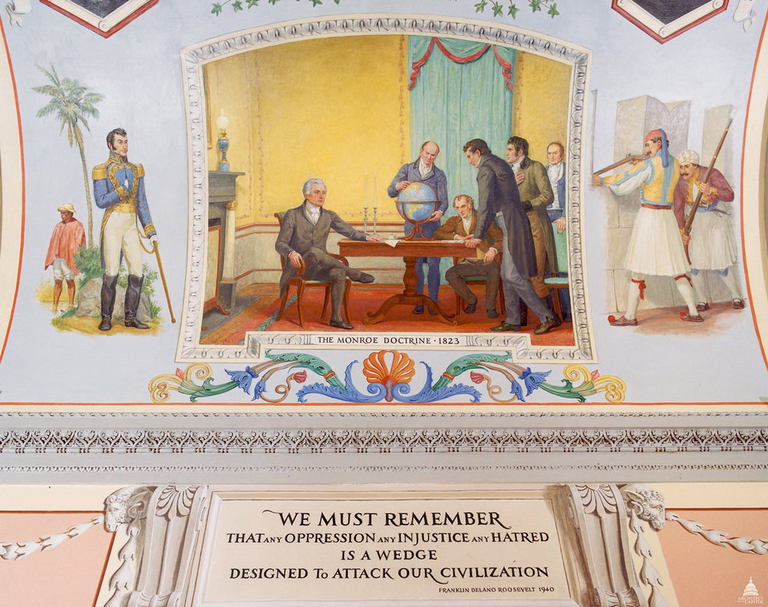

Brother Monroe became characteristically famous for his approach to foreign politics, creating “The Monroe Doctrine” in response to the threat that some European nations might try to aid Spain in winning back her former Latin American colonies. This bold statement aimed to protect the Americas from foreign interference and underscored Monroe's commitment to safeguarding the nation's independence and stability. The Monroe Doctrine became a cornerstone of American foreign policy for generations and reflected his belief in an America that could stand strong and united against external threats.

Domestically, Brother Monroe also played a crucial role in expanding the United States, overseeing the addition of several states to the Union. He supported internal improvements, such as infrastructure projects that connected different regions of the country, promoting economic growth and reinforcing the sense of a shared national identity. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was another pivotal event during Monroe's presidency, as it addressed the growing tensions over the issue of slavery. Though a temporary solution, it demonstrated his efforts to maintain the Union at a time of increasing sectional conflict.

Death and Legacy

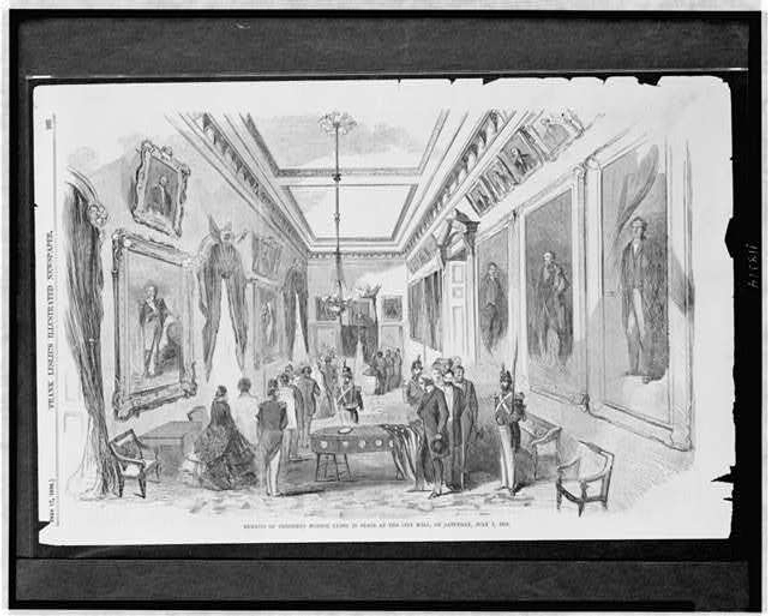

After his presidency ended in 1825, Brother Monroe lived at Monroe Hill, which is now part of the University of Virginia. During his years at his Oak Hill residence in Aldie, Virginia, he hosted notable guests, including the Marquis de Lafayette and President John Quincy Adams. While there, he began drafting a book on political theory, The People the Sovereigns, but eventually set it aside to focus on writing his autobiography. Unfortunately, he passed away before he could complete it. Brother Monroe remained engaged in public service as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830, although he eventually had to step down due to declining health. In his final years, he moved to New York City to live with his daughter Maria before passing to the Celestial Lodge on July 4, 1831, at the age of 73, becoming the third president to pass away on Independence Day.

Brother Monroe remains a testament to what it means to be a Freemason: a man working for the common good. He embraced the ideals of Brotherhood and harmony as he worked hard to bridge political divides, promote unity, and create a government that represented all Americans, regardless of political differences.

Related Stories

Discover additional Scottish Rite blogs and news on this topic.

-

A Jolly Masonic Mug

History

Read More about A Jolly Masonic Mug

-

The Life and Career of Brother Arnold Palmer

Famous Masons

Read More about The Life and Career of Brother Arnold Palmer

-

Manly P. Hall: Philosopher, Mystic, and Freemason

Famous Masons

Read More about Manly P. Hall: Philosopher, Mystic, and Freemason