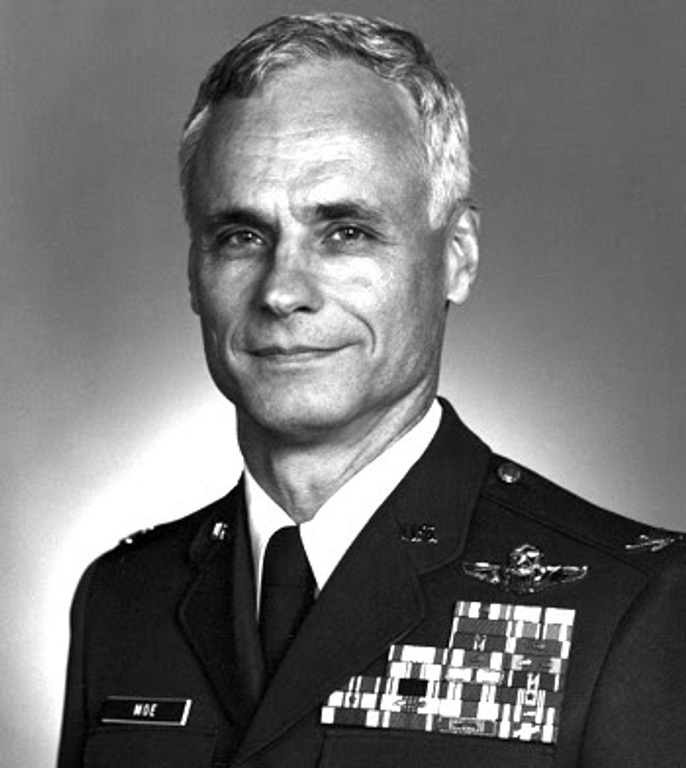

Discover the inspiring story of Colonel and Freemason Thomas Moe, 33° and how he kept soaring faith throughout his five years as a prisoner of war.

By Brother PJ Roup, 33°, Editor of The Northern Light, Active for Pennsylvania

On September 11, 2001, not knowing must have been torture for Brother Tom Moe. His daughter, Connie, was a flight attendant for United Airlines. “I watched, like we all did, the events on television,” he recalled. “Two of the airplanes were United Airlines flights. And we never knew what flights Connie was on.” Brother Moe was no stranger to torture, however, his faith having led him through it years before. But on this day, he faced a crisis.

The crisis wasn’t just over his daughter’s safety but what to ask of God. “I thought to myself, Do I pray that she was not on one of those airplanes? I mean, of course, I hope that. But then I told myself – and I told Connie and Chris later – so if I’m praying that she was not on the airplane, then I am praying somebody else’s daughter was on the airplane.

So God, don’t kill my daughter, kill somebody else’s daughter. I mean, that’s really my thought process.” Tom realized that he couldn’t pray for that. “So I prayed instead for my strength and for hers,” he continued. “That if it was to be that she was on one of those airplanes, that she had strength right up to the end. Right? I couldn’t pray for God to save her, you know, and take somebody else.”

As it turned out, Connie was safe, but from that exchange alone, it was clear that Tom is not an ordinary man. And this was no ordinary interview.

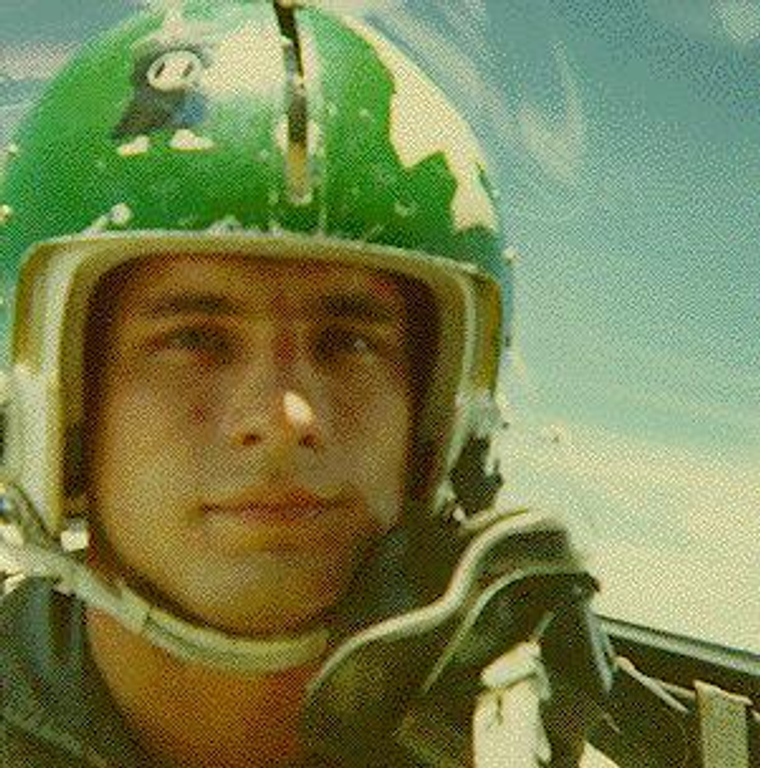

Recently, I was fortunate to sit down with retired Air Force Colonel and Brother Tom Moe, 33°, the most recent recipient of the Supreme Council’s Gourgas Medal. I interviewed Brother Tom at the Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, in the shadow of an F-4C Phantom, much like the one he piloted for 85 missions in the Vietnam War.

Brother Tom is a physically fit, soft-spoken man with deep-set blue eyes that, when he speaks, focus on you like a hawk. His story is one of courage, integrity, forgiveness, and, most of all, soaring faith – a faith made even more remarkable once you get to know the man.

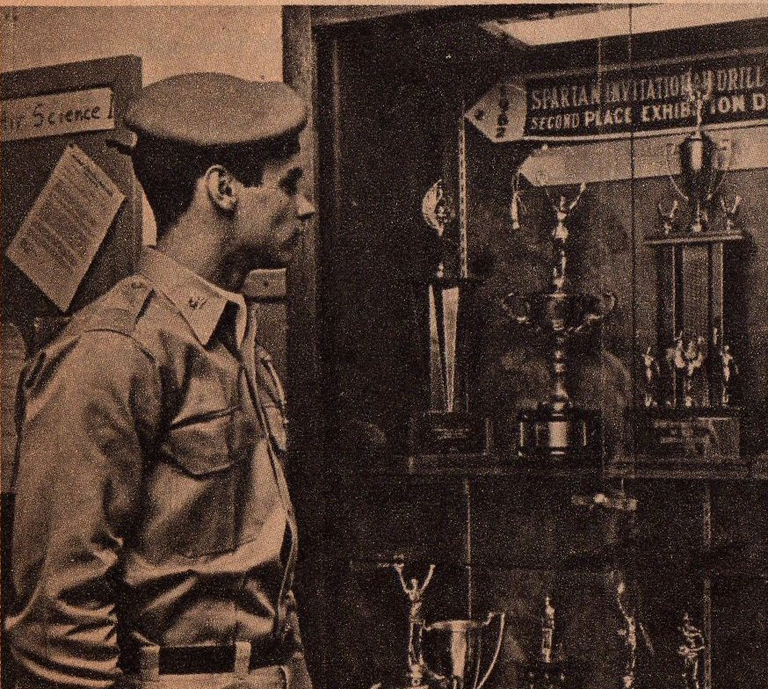

Growing Up

Brother Tom was born in Arlington, Virginia. His dad, a World War II vet, worked for the Department of the Navy. “Looking back, [it was] kind of a Leave It to Beaver type of life,” he recalled. “You know, middle class. My folks didn’t lock the door when the house was empty, we played games, you know, until the sun went down. And it was just a really idyllic life in Arlington.”

As a kid, Tom ran track, played in a band, and met his wife, Chris, in that same idyllic town. “We grew up together – born in the same hospital, went to the same church. All those years, I never dreamed that we’d get married. But we ended up going to college together and we dated a little bit in high school, and then we dated a little more. And lo and behold, 59 years!” he said with a smile.

Tom wanted to be a missionary, having read the Life magazine article about the missionaries who had been massacred in the mid-50s. The inspiration came from the wives who continued the mission and the forgiveness they displayed toward their husbands’ murderers. He didn’t know it then, but understanding that kind of forgiveness would play a pivotal role in his future.

He and Chris both attended Capitol University in Columbus. Tom was already in the Naval Reserve, having been sworn in by his father, who was the commander of the local Seabee unit. He would attend drill on the weekends, while he spent his weekdays in school.

Tom had always had a passion for aviation and eventually realized that seminary – and the life of a missionary – was not for him. As he and Chris began to talk of marriage, he had a decision to make. “She said, ‘Well, if you’re going to be a pilot, I’m not going to marry a Navy pilot.’ All those long cruises and everything,” he explained. “So, I switched to the Air Force Reserve, joined Air Force ROTC, was commissioned as a second lieutenant, and went off to pilot training.”

In the interim, he and Chris got married. He was given a pipeline assignment on the F-4 Phantom, the two-seat workhorse of the Vietnam War. A pipeline assignment meant that he would go to war upon completion of training. Three months before deploying, he and Chris had their first child, Connie.

Off to War

Once stationed in Da Nang, Tom’s primary flight missions were air to ground, focusing on disrupting shipments by bombing roads and forts. Eventually, the pilots began to suspect a problem with the fuses on the ordnance they were using. “So, we started losing flights on these missions,” Tom said. “But we were suspecting the fuse because these losses were occurring at the moment guys were releasing the bombs.” Too much of a coincidence. “In one week, we lost seven F-4s. Seven. Fourteen pilots.”

Tom and his fellow pilots were concerned. “After the loss of these airplanes, we were convinced that the fuses were the culprit. And so we refused to fly with the fuse. We didn’t refuse to fly. There were other fuses, other missions. And, for a while, the leadership didn’t like that because this interdiction mission was important.” Eventually, the leadership relented and sent the fuses for evaluation. In\ January of 1968, they had completed the testing and assured the pilots that all was fine with the fuse. “We didn’t believe them,” Tom said, “but they had done what we asked.” The bombs were put back into the arsenal just prior to Brother Tom’s 85th mission.

January 16, 1968: Mission 85

“And so, lucky me. Lucky those three guys,” he chuckled. “So us four pilots were chosen at random to go on the first mission with the fuse again. And so, with no faith at all in the fuse, we decided to brief a survival tactic.” It was a plan that helped save their lives.

“We flew high. We spread out – not nearly enough, as it turned out. And when it came time to drop the bombs, we did a pull. And I’m watching my wingman as I’m pulling. And, Boom! Just a fireball.” Tom assumed they were dead. “And the nose of the airplane came out of the fireball, and then these two guys ejected as the plane just tumbled out of control.”

Tom quickly realized that his plane was damaged by the blast as well. He found himself with no electronics, no hydraulics, and inverted – a less-than-ideal orientation for ejecting. Recalling his training, he and his other pilot were able to right the plane and eject.

“My emotion was one of absolute anger. I was mad. It happened again. And as I could tell, the four of us survived.” Dangling from his parachute at 18,000 feet, Tom radioed the base and let them know the fuses were still bad. “I want you to know that we just got blown up by our bomb fuses, and you need to tell headquarters right now,” knowing there were other flights following his. The radio operator did just that. Planes en route jettisoned their bombs, and later missions were scrubbed. It is worth noting that this single selfless act may very well have saved other lives.

Brother Tom descended through enemy gunfire and came to rest 40 feet up in a tree. After lowering himself on a cord, he set off running. He realized he couldn’t just keep running. He needed to hide. As strange as it sounds, he managed to evade them at one point by recalling how he used to chase squirrels around tree trunks as a boy.

“I see this really big tree in front of me, and I jump around behind the tree, and I plaster myself up against it. And now it’s like, I hope these guys just go by on one side because I’m going to creep around the tree as they go by. And my heart was pounding like crazy. Like, this is it, folks. And that’s what I did. They came by, and I skirted around the tree.” Even from 10 feet away, they were unaware of his presence.

He spent the first night crouched against a tree, pistol in hand, more worried about tigers than the Vietnamese Army. The ensuing 48 hours were eventful. He was on the radio with a rescue crew as they were shot down in an attempt to get him out in foul weather. The plane exploded so close he felt the earth shake. During the second rescue attempt, he had camouflaged himself under a fallen tree to wait for the planes to take out any threats, as there were troops only a few hundred yards from his position and getting closer.

“They had literally surrounded the log I was under,” he said. “But they didn’t know I was there. They had gone by both ends of the log – this was a big, huge log. So they walked around the log, and they were moving on.” He thought he was safe. “And just as they’re about to take the next step,” he continued, “one of the rescue planes flew overhead again, and they stopped, and they looked up, and then they looked down, and they could see through my camouflage. There I was!”

Tom emerged from his hiding place to a dozen rifles pointed at his head.

1,881 Days

Over the next month, he was moved from camp to camp. “I always acted like I was injured. I’d limp. I’d hold my "back," he said. “I wanted to give the impression to the guards that I wasn’t very mobile, looking for a chance to escape.”

That chance came one night, when none of the guards woke to follow him out to use the bathroom. He made a break for the river only to be spotted by a civilian girl. Tom quickly returned to his cabin as a guard was coming out. “He wanders out, you know, kind of rubbing his eyes. And so, I quickly acted like I was going to the bathroom,” he laughed. “Like what? You know.” A second escape attempt had a similar result.

Tom recalled that the first few weeks of captivity weren’t that bad, relatively speaking. “I had some rather benign interrogations with these guards, and there was no rough stuff or anything. It was, ‘How are you, what are you doing, where’d you come from,’ and so forth. Name, rank, and serial number. It was easy to resist and not tell them anything.”

That all changed when he arrived in Hanoi. During his first nine months in the infamous Hanoi Hilton, Tom did not see a single person except for his interrogators. He would be forced to sit on a tiny stool for days on end. He couldn’t sleep, and the nights were freezing. It was all designed to break him down. They gradually began introducing physical punishment. He found he could roll with most of it, but it eventually devolved into what Tom described as absolute torture.

They tried to offer him an early release, but he refused, saying they must leave in the order they were captured. Their insistence forced him into a hunger strike. “I was either going to die there, or I would look so bad they wouldn’t want to release me. And I really was becoming emaciated."

On discovering that he had been throwing his food away, they tortured him almost to death. “It was like, okay, we’re gonna make up for lost time.” And they did.

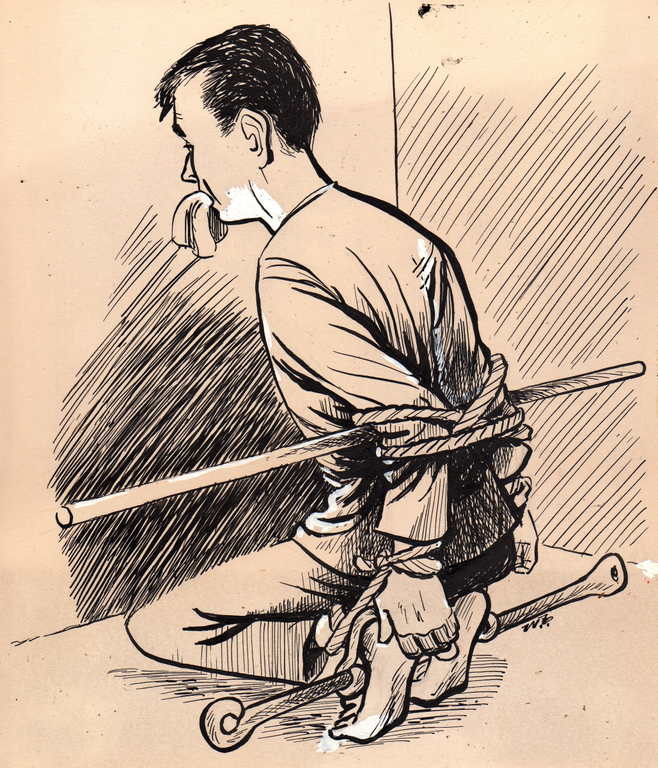

“I knew the stories of torture and so forth were true, but it hadn’t happened to me yet. Most of my problems really were self-inflicted. This time, it got to be seriously applied torture: leg irons, handcuffs, a pole behind your elbows. Your neck is tied to your leg irons, and then you’re just kicked and beaten until you’re unconscious.”

When he was in this pretzel, as the prisoners called it, he found he could survive by placing himself outside his body. He could look down on himself and not feel the pain. “I could see myself being tortured in this room. As I did that, I thought, this is a little scary because I may not be able to come back. And so I tried to walk the tightrope.” Another way he found to survive was to build houses in his head in excruciating detail. He would dig the footer, pour the foundation, lay every brick, and hammer every nail — anything to not be where he was.

He also prayed a lot. “And what did I pray for? I prayed for strength. I didn’t know if I’d come home — I hoped I would come home. I prayed that I’d see my parents and my wife and daughter again. But I prayed for strength because whatever happened, that’s the way it was going to be. And I think God can intervene. I think unbelievable things can happen.”

Soaring faith. Forged in a tiny, dark cell in Hanoi in the midst of so much pain.

Coming Home

Having been tortured literally to the brink of death and having somehow found the strength to survive, Brother Tom knew that it was he who had broken his captors.

From that point, things improved. It wasn’t great, but much more tolerable — live and let live was how he described it.

Things really started looking up in March 1973. Tom was in the courtyard of the Hanoi Hilton and saw a United States C-141 fly overhead and not get shot at. He looked at his friend and said, “That was a good sign!”

A few days later, on March 13, Tom and the rest of the prisoners were loaded onto buses and taken to the airport. “So we get to the airport, we file off, we line up, and we’re just looking straight ahead, very disciplined. And a one-star general was standing there to receive us. He had memorized everyone’s face and name. We get in the 141 [the transport plane that would take them out of Vietnam], and they close the doors.” As Tom tells it, the mood was somber and quiet as they lifted off and made their way toward the Gulf of Tonkin.

“There’s an expression that pilots use as they go over the water that’s called feet wet,” he explained. “So, the pilot hits the intercom. Alright, boys, we’re feet wet! And all bedlam breaks loose.” They were free.

Within a week, he was landing at home at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. He recalled the scene: “My wife, my parents, my little girl, my brother and sisters, uncles and aunts, friends from college, big posters, the other pilot that I had been shot down with, and, it was just really joyous,” he said. “So, one by one, we got out of the airplane and were introduced. I said my few words, and then Chris came running over with Connie and just about knocked me over.”

He was home at last.

Life After the War

There is so much more to this Brother’s remarkable story. Following his release, he earned a Master’s Degree in Government from Notre Dame. He returned to flying as one of the first to pilot the Air Force’s new F-16, and during his 30-year career, he earned 24 military awards, including two Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, two Purple Hearts, and the Bronze StarMedal for valor.

Colonel Moe is so much more than the time he spent in captivity. That time shaped him, but didn’t break him. Rather, it illuminated more clearly the things that are important in life. Today, he is a husband, father, grandfather, and an unflinching advocate for veterans. He is a humble man who looks at his service as duty, not sacrifice. But what about the Freemasons?

A third-generation Mason, Brother Moe was raised in Lancaster Lodge No. 57 and later joined the Scottish Rite in the Valley of Columbus. He was coroneted a 33rd degree Mason in 2017. His connection to the Fraternity runs deep, as he often recalls the symbolic token given to him by his grandfather – an ancient, polished stone with the square and compasses – during a serious illness in his childhood. This token, still in his possession, served as a reminder throughout his life of the values of Freemasonry.

Tom sees Freemasonry as a complement to his faith. “It’s a shared culture, is maybe the way I’d put it best. It’s one more piece of the compass that can help guide you. I like that Masons practice what they preach. It’s a guiding light for all of us.” Those are wise words from a man whose courage, integrity, and faith will forever serve as an example we should all strive for.

Related Stories

Discover additional Scottish Rite blogs and news on this topic.

-

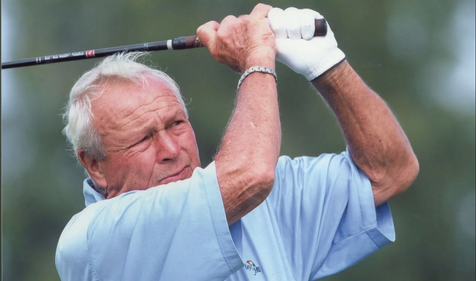

The Life and Career of Brother Arnold Palmer

Famous Masons

Read More about The Life and Career of Brother Arnold Palmer

-

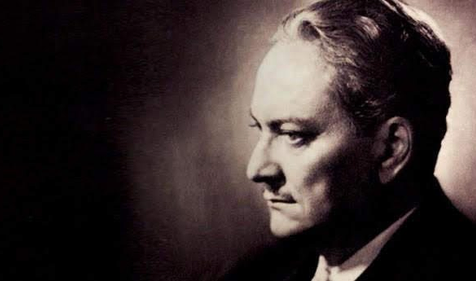

Manly P. Hall: Philosopher, Mystic, and Freemason

Famous Masons

Read More about Manly P. Hall: Philosopher, Mystic, and Freemason

-

What Does the Beehive Mean in Freemasonry?

Degrees

Read More about What Does the Beehive Mean in Freemasonry?